So long, Cloris Leachman. You really knew how to turn it on.

In 1984 I was 23 years old and had a $1000-a-month job working for Susan Shadburne, an independent filmmaker in Portland, Oregon. In those days indie filmmakers outside of LA or New York were rare birds. This was long before Portlandia days.

When Susan hired me, I had a history degree, a broken leg, and no idea what I wanted to do in life. I literally tore out the single Yellow Pages page for film and video companies in Portland and went door to door, address to address. When I hobbled into Susan’s office in a suit and tie, she looked me up and down with a wry smile. I told her that I knew nothing about filmmaking but was willing to sweep floors. As it happened, she needed someone to sweep floors, because she’d written a feature script and was setting out to raise a million dollars and produce it herself.

And she did it. 15 months later, we were actually shooting the film.

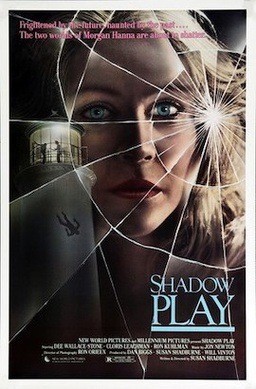

It was called Shadow Play. The script was good enough to attract Dee Wallace (then hot off of major roles in E.T. and Cujo) and, even better, the great Cloris Leachman. The 1970s were her hottest decade, starting with an Oscar for The Last Picture Show in 1971 and then a decade of TV stardom in The Mary Tyler Moore Show and her own spinoff, Phyllis.

Cloris liked to work; some actors pick their roles with a gourmet’s delicacy, but she had a reputation for saying yes to any decent job anywhere. I was a production assistant on Shadow Play, and I ended up driving her to and from our sets around the Portland area. She was a gas, easy to talk with and a little wacky. I can remember bringing her home from our gloomy mansion location late one night — in my beat-up Chevy pickup — and her telling me all about understudying Mary Martin on Broadway as Nellie Forbush in South Pacific. (She really did. You could look it up.) Then she sang an old Kate Smith tune to me, right there in the truck: “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain.”

A few times she asked me to drop her at Delfina’s, an Italian restaurant in Northwest Portland that was the hangout for Portland’s small film community. It seemed she would simply walk in, wait for someone to recognize her — wow, there’s Cloris Leachman! — and then join their table. At first I thought maybe she was lonely, but later I realized, where would you rather be: at home in a rental apartment, or out being Cloris Leachman?

She was unpredictable. One of my fellow PAs told me a story: He arrived to pick her up one morning, knocked, and was startled to see her throw open the door, naked. (She was 59 at the time.) Was it forgetfulness? A seduction? A gag? He had no idea. She laughed and got dressed, and they went to the set.

Cloris Leachman (l) with Dee Wallace in Shadow Play

But none of that is what I really remember about Cloris Leachman. What I remember was watching her act. Shadow Play was a supernatural thriller: Wallace returns to the island where the love of her life committed suicide, tries to make sense of it all and spins out of control. Leachman played the boyfriend’s mother, wounded but empathetic.

It was a juicy role, but that wasn’t the thing. The thing was that Cloris had a way of turning it on for the cameras that was completely unexpected to me. I’m not even sure I can describe it well. It wasn’t manic energy; it was like she powered up the furnace inside, or emitted some kind of vibrations — you could feel it in the room. She jacked it up. It was like watching Willie Stargell crush a fastball.

Cloris Leachman reads tarot cards in Shadow Play

Everyone on that level is a good actor, but in the decade I spent around the business I can remember seeing only two actors turn it on that way: Cloris and then Bruce McGill, a steady-working supporting actor who played the heavy in an HBO movie called The Last Innocent Man, also filmed in Portland. It’s not like he was a fancy thespian — he was a jolly guy who played the motorcycle-riding goofball D-Day in Animal House. But same thing: when the cameras rolled, the circuits lit up.

The first time I was on the set and watched Cloris do her thing, I was actually scared I was going to drop my clipboard or make some sound and blow the shot. In the moment it seemed like some kind of extraordinary event was occurring, never to be repeated. But it turns out that it was actually just a great actor at work.

Cloris Leachman and Thomas Duplessie in Jump, Darling (Big Island Productions / LevelFILM)

Cloris kept right on working; 287 credits, says the IMDB. Her last major role was in Jump, Darling, a Canadian drama which came out just four months ago. One reviewer’s take:

Let’s stop here for a second and savor this for a moment. It’s impossible to watch this film and not think about the fact that Cloris Leachman is 94 years old. N-I-N-E-T-Y F-O-U-R! At that age, most people are either long since passed or snoozing all day in front of their televisions. Cloris, however, is still at the top of the Call Sheet, showing up for work, and delivering powerful performances. Since this is a Canadian film, this American actor has risen to International Treasure status.

It seemed astounding enough to watch her compete on Dancing With The Stars at the age of 82, or even win the Oscar at the age of 44 (considered ripe and old by Hollywood standards) for The Last Picture Show, but her work here truly astounds. Yes, it is very possible the director shot her in isolated closeups a lot in order to feed her lines, but you can’t easily manufacture her presence, her force, and her power. You see every wrinkle, every aging bone, and every slow, careful movement. I savored it, knowing this could easily be one of her last picture shows.

Presence is the word for it. Kinda doubt anyone was feeding her lines, even at the end. What a career.

1984 was a heady year for me, a small-town kid helping get a film made. I was learning what it took to do a job and make it in life. Movie magic exists, it turns out, and I’m grateful I got the chance to see it up close. Thanks, Cloris!