Photo of F. Scott Fitzgerald from The World’s Work magazine (1921), via the U.S. Library of Congress; fanciful illustration by Fritz Holznagel.

Blustery September Saturdays mean it’s time for an annual reading of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s sporting masterpiece The Bowl.

This is not The Cut-Glass Bowl, Fitzgerald’s more famous (and gloomier) short story from Flappers and Philosophers. That story follows a young married couple “through various difficult or tragic events that involve a cut-glass bowl they received as a wedding gift.”

The Bowl is a football story, first published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1928. The narrator is a Princeton grad, too skinny to make the college football team, looking back on his friend and roommate Dolly Harlan, who was a football hero but a reluctant one:

Perhaps the worst of it was that he wasn’t really a star player. No team in the country could have spared using him, but he could do no spectacular thing superlatively well, neither run, pass nor kick. He was five-feet-eleven and weighed a little more than a hundred and sixty; he was a first-rate defensive man, sure in interference, a fair line plunger and a fair punter. He never fumbled and he was never inadequate; his presence, his constant cold sure aggression, had a strong effect on other men. Morally, he captained any team he played on and that was why Roper had spent so much time trying to get length in his kicks all season–he wanted him in the game.

“A fair line plunger” — not a thing that ESPN analysts say much these days. The Bowl is loaded with old-fashioned touches like that. Of course, as the Hartford Courant notes, the game was a lot different in those days:

The college game [of the era]… was more like rugby. The ball was shorter and rounder, so it bounced truer and the drop kick, which could be attempted at any time, was a prominent three-point weapon… Forward passes could be attempted only from five yards or more behind the line of scrimmage. The quarterback did not squat under center; the ball could be snapped to anyone in the backfield, not unlike the wildcat we know today. It was orchestrated chaos.

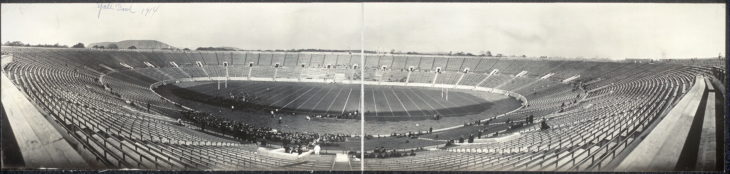

1914 photo by J.H. Candel, via the U.S. Library of Congress

The “bowl” of the title is the Yale Bowl, a marvel of its kind when constructed in 1914 with a then-amazing capacity of 70,000. It’s still in use today, and part of the National Historic Register since 1987.

But in a larger sense, the bowl is the field of human achievement. It’s Teddy Roosevelt’s beloved arena, where the man “whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood” strives for victory. As Dolly Harlan describes the struggle in the story:

“Yale would punt and I’d look up. The minute I looked up, the sides of that damn pan would seem to go shooting up too. Then when the ball started to come down, the sides began leaning forward and bending over me until I could see all the people on the top seats screaming at me and shaking their fists. At the last minute I couldn’t see the ball at all, but only the Bowl.”

This being an F. Scott Fitzgerald story, there’s also young love, nostalgia tinged with melancholy, and a whole lot of upscale society wealth — a world where it’s normal for college students to drive into New York City on Saturday night and then hand the car over to the family chauffeur. (It’s Princeton, after all.) Fitzgerald loves his dreamy aspirational thing, and he has to be taken as he is. Nobody playing college football today is like any of the people in The Bowl. (At least, not since 1968.) It’s not a story for modern times.

All the same, it’s terrific writing and, near the end, has some especially emotional game descriptions that make me tear up just a bit every time. I do choke up easily, but that’s still saying a lot for a short story from 1928. If you get nostalgic at all this time of year, try The Bowl.